Medieval wills are precious mines of information for historians, art historians, scholars of fashion and material culture, but also for sociologists, anthropologists, economists.

Behind the dryness of notarial formulas lie glimpses of real life—human relationships, emotions, hopes for life after death, and for the lives of those who would remain on Earth. Journeys and ventures of various kinds often loomed on the horizon for those who decided to set down their final wishes in writing.

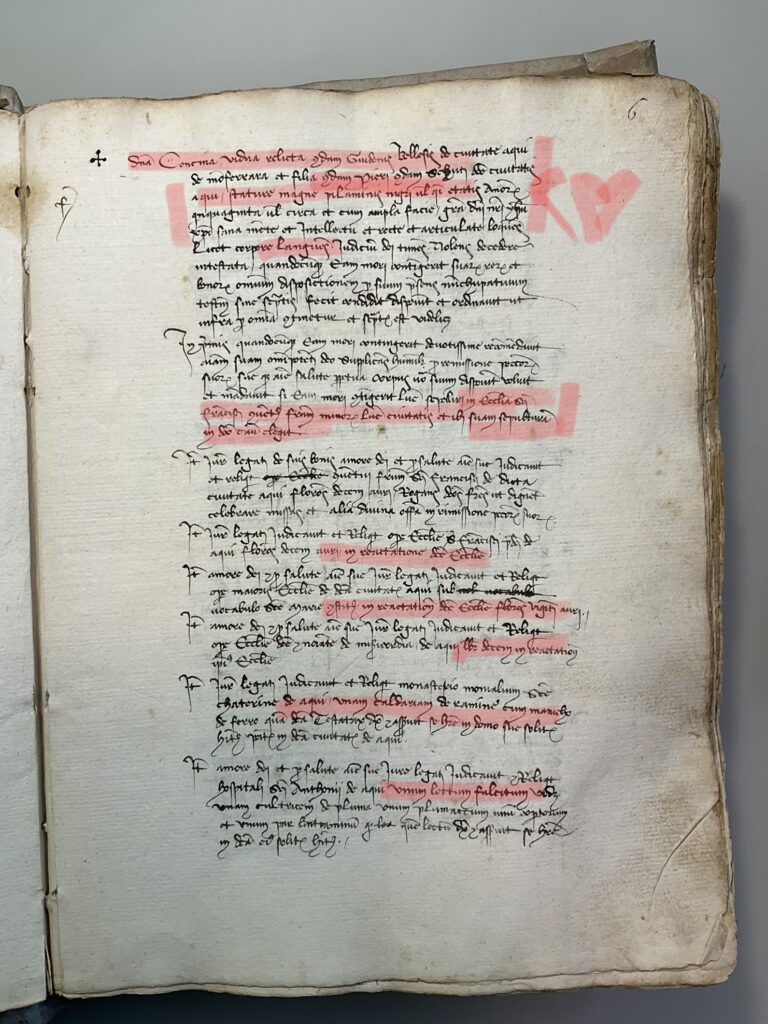

(traces of digital highlighting on picture – no parchment has been harmed in the process!)

The unknown at their doorstep, the fear of dying intestatus (without having made a will), pushed men and women to put their earthly and spiritual affairs in order. Old age or a feared terminal illness could prompt this, but so too could journeys of different kinds: pilgrimages, business missions, enlistment in the army, or a pregnancy—perhaps the first—and the imminent birth, at a time when the lives of both mother and child hung by a thread.

Beyond the necessity of distributing properties and legacies, the will also tells of the tenacity with which men and women tried to defy the oblivion that death brings with it. Our project studies precisely this desire for memory, this need to be remembered by one’s community of belonging—through objects meant to endure over time and to be displayed in public and semi-public spaces.

Objects of memory, in short. Objects which, in most cases, have been lost.

Every day, we delve into this yearning for eternity, for overcoming human finiteness. Sacred objects, places of worship and hospitality, books, bells, beds, clothing—inscribed in all these donations is the desire for remembrance of medieval men and women.

Among them are also wax statuettes depicting the testator—or more often, the testatrix… because women more than men seem to have wanted to leave behind a memory of their image in wax. These are objects rarely mentioned in wills, and for that reason, they are precious testimonies of both the devotion of the donor and the relationship men and women have with the fragility of the body and the flesh.

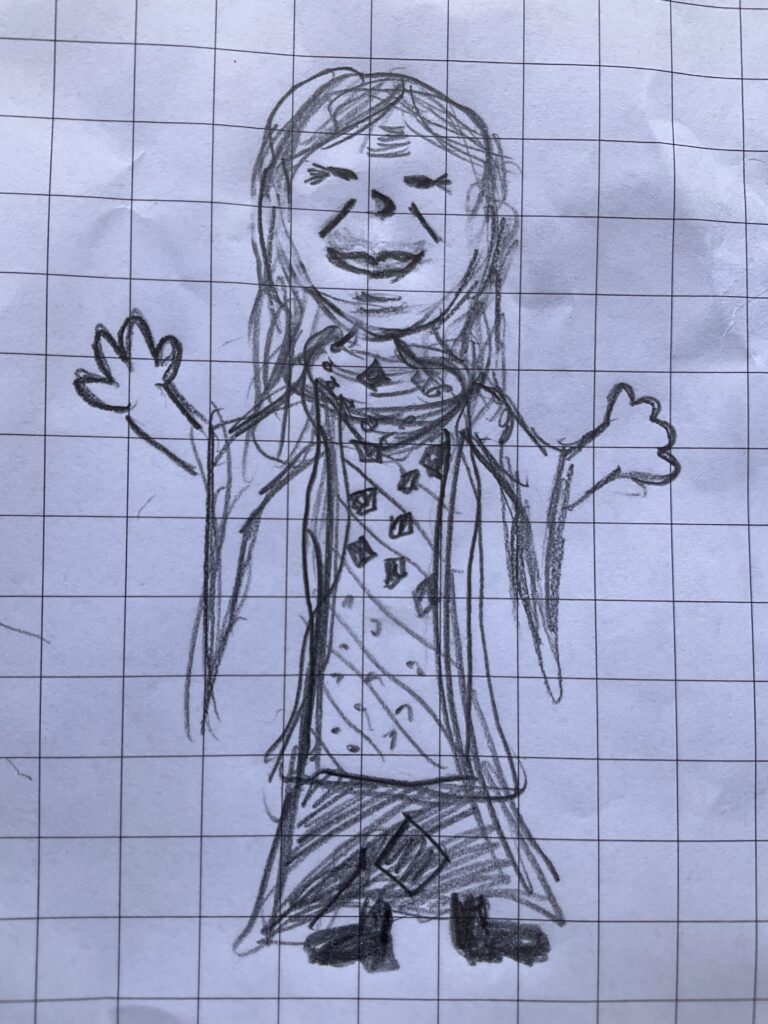

Unique, however, is the portrait with which a woman in the 15th century opened her will. Concima, a widow and domina from Acqui, who presumably fell ill while passing through Lucca, described herself as a tall, dark-haired woman in her fifties, with some white hair and an open, spacious face. A woman likely of striking appearance—a presence hard to overlook—and one who, with an unexpected and completely unnecessary portrait, defeated time and oblivion.

“Domina Concima […] stature magne pilaminis nigri vel quasi etatis annorum quinquaginta vel circa et cum amplia facie“

And here she is – nearly 600 years later Concima is still being talked about. Her portrait was entrusted to the hands and imagination of an 8-year-old girl. Thanks Milena for this “miniature of tall Concima”… although I’m not sure how happy she’d be about being shrunk that much!

byValentina Costantini