This New Year’s post begins with a homicide.

In March 1389, early in the morning, the notary Giovanni Gini and the second-hand dealer (rigattiere) Romolo Bartolini were sent by the Florentine hospital of Santa Maria Nuova to the house of Gemina, located opposite the residence of the noble Agnoli family. Gemina was the third wife and widow of Manetto da Filicaia, a woman of respectable social standing. A year earlier, she had drawn up a will naming the hospital as her universal heir and beneficiary of her household goods (masseritie) —a common practice in medieval society from the mid-Trecento onward, especially in Tuscany.

Alerted to her death, perhaps by neighbours or relatives, the two men found her lying on the ground, mortally wounded. The notary, charged with inventorying the hospital’s inheritance, recorded the scene with chilling brevity: “She died during the night… and I saw her head crushed.” Much of her property had already been stolen (“…and we found very little among her belongings”). What remained were everyday objects—knives, scissors, sewing tools—alongside beds, a few chests of various sizes, linens, shoes, and women’s hoods: the possessions of a woman of some standing, even after the theft.

Her will (preserved in one of the hospital’s books of testaments) does not specify which items she intended to leave to the hospital, but some valuable ones were likely among the missing goods. Among her masseritie, she may have included a sacred painting or a tabernacle. Some inventories do, in fact, mention art and devotional objects among donated goods – although they are rare before the mid-sixteenth century. Like others, Gemina may have intended to bequeath a tabula de nostra donna (an image of the Virgin), to be placed in one of the hospital’s rooms, near the bed of a sick patient. Unfortunately, we will never know.

Why tell the story of Gemina’s tragic fate and her post-mortem inventory? There are two reasons, both connected to: (a) how and where we encountered Gemina’s story, and (b) how these findings shaped A&I’s first steps into the new year’s agenda:

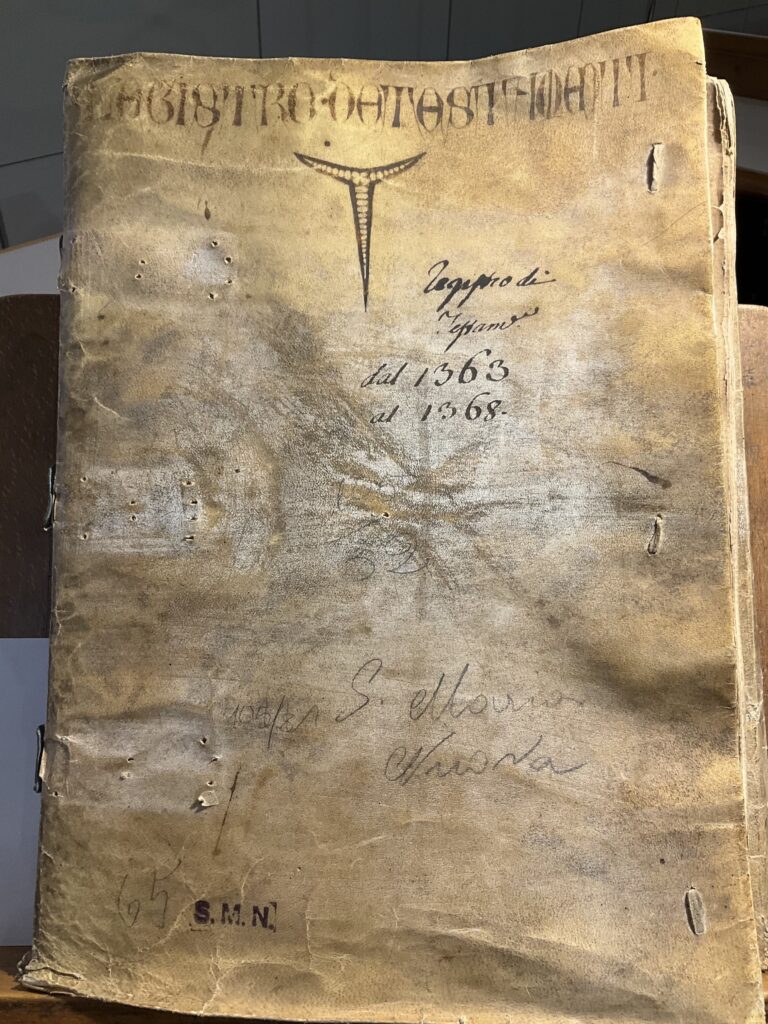

Let us begin with the source (a). The story goes back to autumn 2023, when—together with friend and colleague Serena Galasso (University of Padua, ThiMa, MSCA, 2025–2027)—we were searching for objects bequeathed pro remedio animae in the archives of churches and hospitals. Although we did not find exactly what we were looking for, the research led us somewhere unexpected. And now, after postponinig it for far too long, Serena and I are finally completing a paper on what we have been finding and cannot say much more. You’ll have to stay tuned: the paper will be presented and published later this year, when also the new inventory of the Florentine hospital of Santa Maria Nuova is completed by the archivists currently working on it.

This leads us to the second point (b): how Gemina’s story and the hospital’s sources we’ve found have also informed A&I goals for 2026, as the project enters its fourth year. While still coding testaments from Lucca, Perugia, Venice, Dubrovnik, we will conduct a quantitative and qualitative study of objects of art and devotion in post-mortem inventories from 1340s up to 1525, when our research ends. Through these still largely unpublished records, A&I will also been involved in a broader project on the execution of testamentary dispositions (Beyond the Will: The Execution of Pious Dispositions in the Late Middle Ages: Managing and Governing pro anima Investments through Economy and Pastoral Care ), which will result in a special issue of Quaderni di storia religiosa medievale to be published in 2027.

Beyond wills, inventories and executory documents offer a complementary way of reading late medieval society. Hospital archives—especially in Italy—are an unusually rich mirror of the world around them: they preserve the traces of the humble, the voiceless, and many women who are otherwise difficult to find in historical sources.

So here’s to the new year. May it be—for us, and for you who read us—a year as rich in discoveries and satisfactions as the one just ended.

Valentina Costantini