I have just returned from a short stint in the Archivio di Stato di Firenze (ASF), 18 September to 2 October. It may be my last archival collecting of testaments for the project, at least in the ASF. The purpose was to increase the sample size of my last quartile of Pisan testaments,1501-25. These records within the Notarile Antecosimiano remain in Florence. In my previous trip to the ASF (January and February 2025), I had decided that there was little to gain by searching for more testaments in that quartile, although it contained only 35 testaments, while most of my other chronological units exceeded two hundred testaments.1 From 35 testaments, it was clear testamentary commissioning of objects in public places had dropped drastically. Moreover, for Pisa, unlike in Florence, the sharp decline had also impinged on elites. As other members of our team have experienced, the search for testaments after the mid-fifteenth century, when commissions become scarce, can be not only boring but also dispiriting.

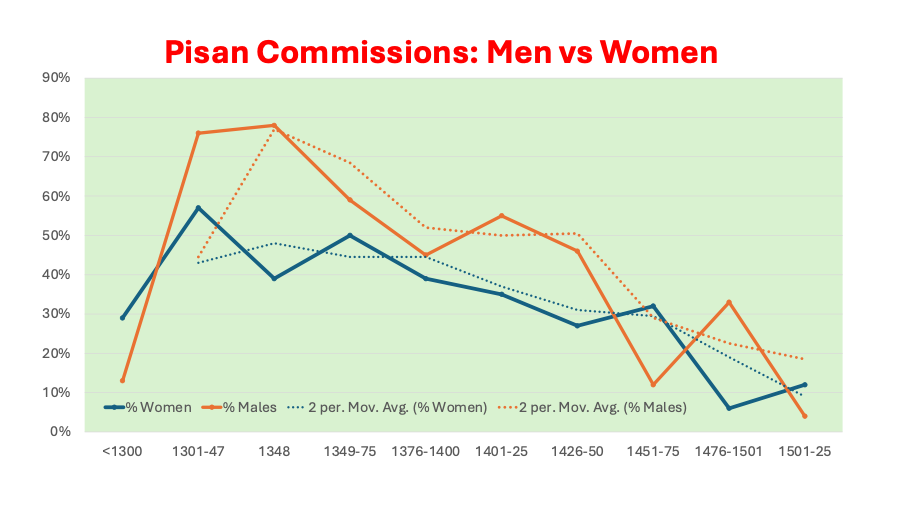

However, when returning to Scotland and analysing the data I had collected, I discovered a curious tail end to the otherwise steady decline (1) in the percentages of women drafting testaments, (2) the proportions of married women testators to widows, and (3) the commissioning of art objects. In the last 25 years of my Pisan samples, all three trends reversed direction and nudged upward; women’s commissioning even surpassed those of men. But could this small sample of only 35 wills be trusted? Ergo, I returned to the ASF after our third annual meeting and boosted the quartile 1501-25 to 200 testaments. In addition, I had time to turn to the second lowest quartile (1476-1500) and raised it from 82 to 190 testaments.

Was the effort worth it? Two of the three trends taken from the previous sample changed convincingly: the decline in women testators relative to men in this last quartile had not swung in the opposite direction as earlier charted but instead had stabilized at the lowest point with the penultimate quartile,1476-1500, at 25%, half of what they had been in the early Quattrocento following Florence’s conquest of Pisa. Second, although the proportion of women’s commissions outstripped men’s, men had not vanished as commissioners as the earlier sample had charted. Instead, men’s and women’s commissions were the same (despite men redacting almost two-thirds of these testaments). However, the new sample of 200 charts two traits in common with the earlier one of 35: the percentage of married women to widows rose (in the case of the larger sample from 8% to 31%), almost reaching their rates before Pisa’s loss of independence (36%) ; second, the number of married women’s commissions equalled those of widows and men, despite their lower number of testaments. This relative strength in women’s commissioning finds no parallels in Pisa’s previous history or for any other regions we have thus far investigated.

What can we make from these trends? First, Pisa’s political and social experience of the years 1501-25 was brutal even within the general Italian milieu of the plagues in the 1520s and an increase of sacks of cities and villages with the intensification of the Italian wars. From 1494 to 1509, Pisa was at war with Florence. It was a struggle led by the popolo for independence.2 Given this constant warfare, the number of surviving notaries declined. Yet their notarial books continued to contain numerous acts of everyday life and commerce (sales and rentals of land, marriages and dowry transactions, dispute settlements among neighbours, congregations of monasteries and priests to approve reforms, etc.) In this struggle, women performed essential roles, in fact, ones that diplomatic dispatches and narrative sources highlighted more than for any other revolt in Italy over the Middle Ages or early modern period, including the Neapolitan revolt of Masaniello in 1647, when women were initially a major force of the rebellion. Pisan women during their revolt from 1494 to 1509 had gone further. Early on, they elected ten women captains with fifty women to serve under them to maintain Pisa’s walls and fortifications, while other women organized and led their own military division comprised of well-armed women who gained praise for their skill and courage, even from their enemies, such as Florence’s Francesco Guicciardini in his Storie fiorentine and from diplomats as far away as Venice.3

Here, I speculate that the revolt against Florence revitalized the independence of women and their liberties, harking back to as early as the thirteenth century as evinced in testamentary practices and by Pisan statues. In contrast to Florence and most other cities in Tuscany, Pisan women were not required to assign male protectors (mandualdi) to represent them in a wide variety of notarized contracts. Nor was the consent of their husbands necessary to redact a will as appears in Florentine wills. Furthermore, husbands and married women were equals in their requirements of bequeathing 15 lire to one another in their testaments, a practice that continued well after Pisa had become a dependency of the Florentine territorial state in 1406.

The independence and strength of women is further attested within testaments. From the late thirteenth to the mid-fifteenth century, the proportion of women testators was almost the same as men’s, in contrast to Florence and other towns and villages across its territorial state. In Florentine Tuscany, women testators comprised only a third, and in towns and villages of the Florentine contado, such as Carmignano, their proportions were smaller. Moreover, until the mid-Quattrocento, the ratio of married women testators to widows in Pisa also exceeded other places in Tuscany. Before 1450, widows comprised less than two-thirds of women testators, while in Florence over 90 percent of women testators were widows, paralleling Diane Hughes’s claims about late medieval Genoa: women came of age only after their husbands had died. Although widows in pre-twentieth century Europe could certainly be young, married ones on average would have been younger and more likely to have been the ones organizing the repairs of Pisa’s fortifications or to joining the city’s all-women’s military units during its war for independence.

Photo Credit: G. Bettini

One testament discovered in my extension of the last quartile cuts against the loss of women’s independence in drafting their wills and commissioning art since the 1450s. At the same time, it may reflect a revival in women’s earlier sense of independence sparked by the Pisan revolt and women’s role in that fifteen-year conflict. On 12 December 1510 (1511, by Pisan dating), the prudent and chaste (prudenta et honesta domina) Lucrezia [Lucresia], daughter of the deceased Mariano from Cremona and wife of Onofrio, a goldsmith and citizen of Pisa, son of Agostino, son of Valentino, drafted her testament. She identified herself as a tertiary of the Franciscan order and chose to be buried in the Observant Franciscan church of Santa Croce, just beyond Pisa’s city walls in the claustra “where other tertiary women were buried”.4 She was one of only nine married women of 200 testators to make a will in my 1501-25 sample. Yet she commissioned two of only twelve commissions in this quartile. Moreover, she was the only one in the period to commission a painting or order the construction of an altar or chapel. In addition, only two other Pisans in this quartile made more than a single commission and as with Lucrezia made only two.

These choices were freely hers. No stipulation appears in her testament, asking for consent of her husband or from a previously elected mandualdus, although by the sixteenth century contracts for women to engage mandualdi finally surface in Pisa’s notarial records. 5 Indeed, her husband appears only in the notary’s identification of Lucrezia and in her two commissions, where she places demands on him. In addition, Lucrezia did not elect him as her universal heir but chose instead three women, none of whom showed any blood relationship to her or her husband. She leaves him nothing, not even the statutory 15 lire required of spouses.

Lucrezia’s first commission ordered the construction of an altar in honour of God and Saint Francis in Pisa’s nunnery of San Bernardo for the relatively small amount for an altar of 20 ducats (then equal to 35 florins).6 She demanded that her husband pay the sum from her marriage gift (“de meis donamentis), which he had owed her. Her second commission ordered “the making” of a panel painting for her new altar, in which three figures—”the Virgin Mary, Saint Francis, and Saint Elisabeth [of Hungary], the patron saint of the Franciscan tertiaries”—were to be “made’ and completed within four years. Again, her husband was responsible for the payment–100 lire (5 florins), owed to her again from her donamentis. She then held him accountable to oversee that two nuns at San Bernardo (who were also the two of her three universal heirs) would ensure the chanting of weekly for Lucrezia’s soul. She mentioned nothing regarding her husband’s soul.7

Moreover, five of the twelve commissions in the last twenty-five years of the Pisan sample came from women. Although small in number its ratio to male commissioners surpassed every period from Florentine Tuscany outside the Pisan territory. However, unlike my earlier sample of 35 (where no male commissioners appear), men in the later sample were engaged in commissioning in equal numbers to women. Finally, Lucrezia’s commissions show originality: in having now read circa 10,000 testaments, I have found none to name a chapel or altar after the pair God and Francis and have discovered none to commission a panel or wall painting combining the three figures–the Virgin Mary, Francis and Elizabeth of Hungary, either as a trio or with other saints. And the third saint in this trio, Elizabeth of Hungary, despite her origin, was no stranger to Tuscany as witnessed by Simone Martini’s multiple paintings of her during the early fourteenth century.

In conclusion, my arguments may appear contradictory. On the one hand, I am arguing for larger samples of testaments than have been standard over past several decades, especially for late medieval and early modern studies of testaments. On the other hand, I have given considerable attention to a single will as a precious peep hole into the past. My point here is that these peeps can be more than illustrations of statistical series to put flesh on the bones of numbers. They can cut against the grain of statistical series and provide new insights into the past. But either way, the significance of such examples could not have been recognized without the long and sometimes dreary collection of hundreds of documents to establish what was typical and what was growing against the grain and why it was doing so.

- That is for 6 of these periods. There were fewer for 1051-1300 (117), 1326-47 (118), and 1348 (44), but for these I had already consulted all the notarial books indicated as redacted by Pisa notaries ↩︎

- On the Pisan war, see Michele Luzzati, Una guerra di popolo: Lettere private del tempo dell’assedio di Pisa (1494–1509) (Pisa: Pacini editore, 1973). ↩︎

- See Cohn, Popular Protest and Ideals of Democracy in Late Renaissance Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022). ↩︎

- From my sample of testaments, the cemetery of this convent became particularly popular only by the last years of the fifteenth century and especially in the first quartile of sixteenth century and was chosen as the “campo sancto” principally by women ↩︎

- See for instance ASF, Notarile Antecosimiano, no. 12667, 6 May 1515 (Pisan style), 19v-20r; others can be cited. ↩︎

- ASF, no. 12667, 27 November 1518 (Pisan style),161r-v ↩︎

- Ibid. no. 6029; 12 December 1511 (Pisan Style), 33r-4r. ↩︎

Samuel Cohn